OBBB’s Reckoning for Wind and Solar

This essay explains why new wind and solar projects are expected to decline sharply over the next two years as the OBBB’s strict tax credit rules, supply chain restrictions, and aggressive enforcement drive up costs and risk. With subsidies set to expire after 2027 for new projects, the decades-long era of easy tax-driven renewable energy development is coming to an end.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) marks a major shift in U.S. energy policy—one that places American taxpayers and national interests squarely at the center of federal energy incentives. For too long, generous tax credits for wind, solar, and battery projects disproportionately benefited developers and tax equity investors, often with little scrutiny over whether those projects served meaningful economic or national objectives.

Under the new law, eligibility for the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and Investment Tax Credit (ITC) has become far more complex and legally uncertain. That’s by design. The OBBB prioritizes strengthening America’s energy system with reliable, dispatchable power—not tax-driven projects that weaken the grid’s resilience.

For tax equity investors—whose participation depends on predictable tax credit monetization—this new environment is especially risky. Without assurance that a project will ultimately qualify, many may refuse to invest. Legal opinions that once provided comfort may now come with significant qualifications, leaving developers and investors navigating far more uncertain terrain.

At the heart of this shift are three critical risks: stricter scrutiny of what qualifies as “beginning construction,” tough new supply chain rules aimed at eliminating dependence on Foreign Entities of Concern (FEOCs), and an aggressive enforcement mandate delivered by executive order.

The sections below explain how these reforms work together to protect taxpayers, reduce federal exposure to questionable projects, and ensure that any future renewable development serves America’s long-term economic and national security priorities—not just the financial interests of developers and investors.

Guarding Against Gamesmanship in the Construction Timeline

One of the most immediate risks centers on how—and when—a renewable energy project is deemed to have “begun construction.” The OBBB codifies the IRS’s longstanding tests—the Physical Work Test and the 5% Safe Harbor—as they existed on January 1, 2025. But codification should not be mistaken for certainty. Key terms like “physical work of a significant nature” remain undefined in both statute and guidance, giving Treasury ongoing discretion to interpret or narrow their application.

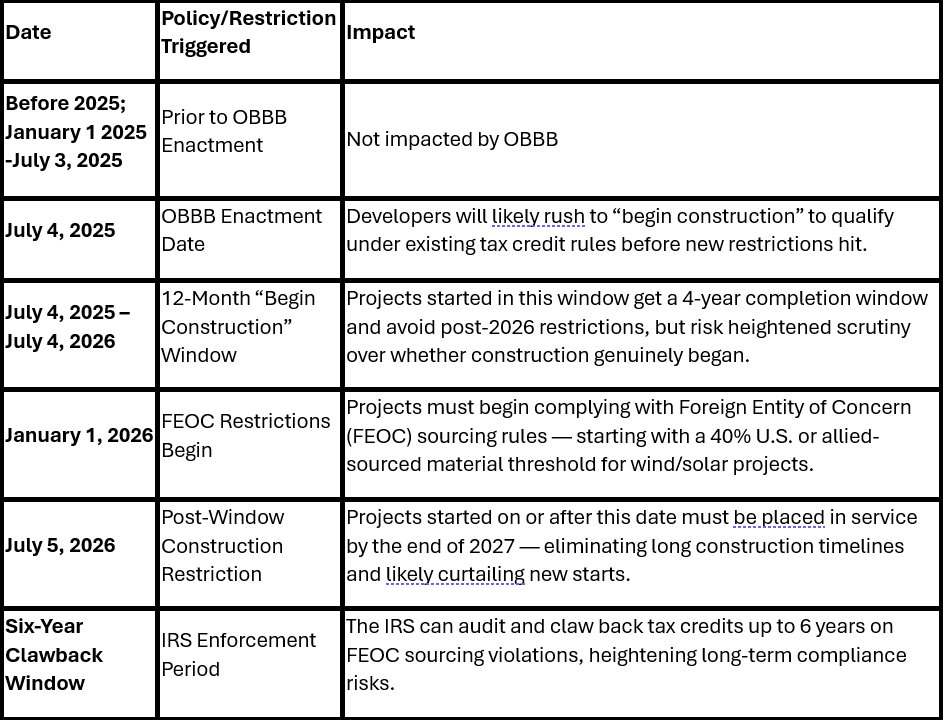

Timing is critical. Projects that begin construction between July 4, 2025, and July 4, 2026, have a four-year window to complete construction and be placed in service while still qualifying for credits. Any project that starts on or after July 5, 2026, faces a hard deadline—completion by the end of 2027—or it forfeits eligibility for the PTC and ITC. This compressed timeline is likely to sharply reduce new project starts after July 4, 2026. (See Table)

This looming deadline creates predictable pressure on developers to lock in their construction start dates during the 12-month window following enactment. However, developers and investors must understand the limits of the safe harbor protections. The four-year safe harbor only applies to the continuity requirement—that is, assuming construction genuinely began, the IRS will not second-guess whether the project progressed continuously if it meets the deadline.

But the IRS still retains full authority to examine whether construction genuinely “began” in the first place. If the facts suggest that a developer’s claimed start of construction was superficial, premature, or staged merely to preserve tax credit eligibility, the IRS may disallow credits retroactively—regardless of whether the four-year window was met.

Developers and tax equity investors must be prepared to substantiate not only that they met the timeline but that they genuinely satisfied the start-of-construction standard with credible, documented evidence of real construction activity. Anything less leaves the project—and the tax credits—exposed to challenge.

A Long-Overdue Reckoning for Foreign Supply Chains

The second major compliance challenge comes from the OBBB’s new restrictions on the use of materials and components sourced from Foreign Entities of Concern. For years, renewable developers relied on opaque global supply chains—especially in China—for solar panels, wind turbine parts, and battery components. These foreign sources often have ties to forced labor, military-linked entities, or regimes hostile to U.S. interests.

Wind and solar projects that start construction in 2026 and expect PTC or ITC support must meet a strict Material Assistance Cost Ratio (MACR) threshold: at least 40% of direct material costs must come from non-prohibited sources. For projects starting construction in 2027 the ratio increases to 45%.[1] Failing to meet the threshold disqualifies the project from federal tax credits.

This compliance burden will drive many developers to accelerate their construction start dates into 2025, before the FEOC restrictions kick in. The OBBB’s statutory anti-circumvention language grants Treasury sweeping authority to conduct audits and deny credits subject to lookback periods up to six years even if construction tests appear satisfied—based on “facts and circumstances.” Activities that once sufficed, such as stockpiling equipment or off-site prep work, may no longer be viewed as legitimate. Developers who start construction in 2026 must secure sworn certification from every supplier—under penalty of perjury—that no component or subcomponent was produced by, on behalf of, or controlled by a prohibited foreign entity.

OBBB Policy Timeline

Executive Order: A Broader Mandate for Strict Enforcement

On July 7, 2025, President Trump issued an Executive Order (E.O.) amplifying the OBBB’s enforcement agenda. The E.O. directs the Treasury Department to take “all action as the Secretary deems necessary” to prevent manipulation of both the FEOC compliance requirements and the construction start tests—even in cases where the statute itself is silent.

The E.O. reinforces the OBBB’s core objectives but does not expand Treasury’s legal authority beyond what the statute provides. Instead, the EO signals the administration’s clear intent to enforce the law aggressively, particularly regarding “begin construction” compliance and foreign supply chain restrictions. While the EO cannot create new penalties or rewrite statutory definitions, its real impact lies in shaping agency behavior—prioritizing strict audits, tougher guidance, and heightened regulatory oversight. In this sense, the E.O. magnifies the compliance risk developers and investors face under the OBBB, even though it does not alter the legal framework itself.

The E.O.’s mandate ensures that even technically compliant projects may face rigorous scrutiny—and potential retroactive challenge—if the government questions the substance of their construction start or supplier certifications.

Conclusion: The Reckoning Has Arrived

The OBBB and its companion Executive Order create a regulatory environment defined by aggressive oversight, stricter compliance demands, and real financial consequences. The dual burden of proving construction compliance and navigating complex foreign supply chain restrictions—often years after tax credits are claimed—will transform clean energy finance into a riskier, more disciplined endeavor.

For investors, the stakes are higher than ever. Without solid legal opinions, verifiable supplier chains, and consistent enforcement policies, many may choose to exit the market. For those who stay, the cost of risk will rise—along with the overall cost of renewable energy deployment.

And that’s exactly the point. For years, critics warned that renewable subsidies enriched private developers while delivering uncertain public value. The OBBB responds to those concerns by closing loopholes, demanding verifiable construction, and limiting reliance on hostile foreign suppliers. We can expect the result to be fewer speculative projects, more disciplined accounting, and a market correction long overdue. For Americans seeking reliable, affordable, and sovereign energy—this is the reckoning they’ve been waiting for.

[1] For energy storage projects, the MACR threshold begins at 55% in 2026 and rises by 5 percentage points annually, reaching 75% for projects beginning after 2029.